Names on the Wall

On the Sunday when the nation pauses briefly to remember the horrors and sacrifices of wartime, I’m posting a piece I wrote in high summer. A visit to Adlestrop, made famous by lines written by the war poet Edward Thomas, led me to reflect on loss and the cruel impact of conflict.

Adlestrop’s church is small-windowed, with a roof of Cotswold stone tiles. When I step inside, the muffled ticking of its clock mechanism only serves to amplify what Larkin calls the ‘unignorable silence’ of places such as this. Some tired looking postcards don’t appeal. I don’t dwell on the visitors book, except to notice that friends who were here last week didn’t record their presence.

Halfway down the aisle, I look up at a lozenge-shaped crest of the Leigh family, advertising their patronage. Its once proud red and gold colours are now faded. On the right half of the crest, three black moles – dormant, in heraldic terminology - catch my eye. Apparently, their blindness signifies the ability to keep a secret. Who knows what the Leighs of old needed to keep hidden?

Speak to me, moles. Tell me your secrets.

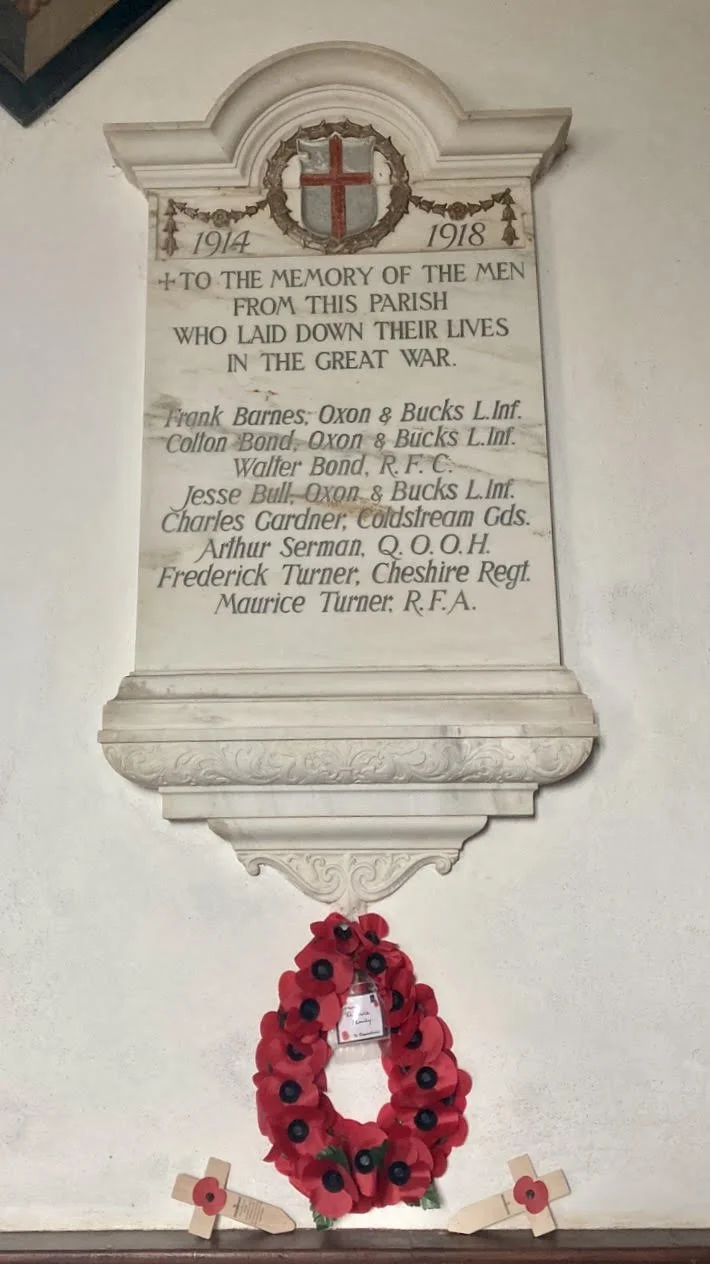

Just beyond the crest, and set a little lower on the wall, is an alabaster memorial. It’s what I’ve come to see. There are eight carved names, this place’s sacrifice to the Great War cause. Eight may not sound many, but from a tiny village that’s a heavy offering. Every villager would have known these young men. Perhaps that explains why ranks are omitted, Christian names are given, dates are not included. The truth of the memorial is starkly clear, for all the lack of detail.

Speak to me, names on the wall. Tell me your stories.

I walk away from the church, taking a narrow lane towards the railway line. Gatekeepers flutter about the hedgerows, and a yellowhammer sings half-heartedly in the rising heat of the day. Soon enough, I emerge into a meadow, where tall grasses and the wildflowers of early summer have been scorched to a light sand uniformity. It comes as a surprise to see the bright green of an enclosed cricket ground. The well-watered square in particular shows no sign of the recent dry spell. If the age of the tractor and gang-mower is anything to go by, cricket has been played here for generations.

It’s in the club’s pavilion that the Great War harvesting of one of Adlestrop’s generations really hits home. By chance, the low-slung building is open. Club stalwart Derek Hedges (chairman, groundsman, long time player) is inside, tidying up after the previous evening’s game. But he’s happy to talk with me about the village and discuss how the pitch plays. His advice? ‘If you don’t try to rush things, you’ll get runs.’ Finally, we look at the old team photos on the wall.

The picture of the 1924 team, complete with names, demands my attention. A few places apart on the front row are Ted Bull and Bill Barnes, both staring directly and pensively into the camera lens. As well they might. Because these two, surely, reveal a link with the war memorial in the church. They must be younger brothers of Jesse Bull and Frank Barnes, two of the names on the list of Adlestrop’s war dead.

Derek and I muse on the likely connection. Our thoughts collide. Did Jesse and Frank know the joy of village cricket before they left for war? Who in that worn photo witnessed the horrors of the Western Front? Did any have a brush with death? Did cricket, with its unique mix of camaraderie and quiet phases, help Ted and Bill to remember? Or were they wanting to forget?

Speak to me, Ted. Speak to me, Bill. Tell me how it was.

Derek and I found no answers, only questions. But at least by asking the questions, we remembered.